Calorific Value of Biogas: LHV vs HHV, Ranges and Units

Learn about the calorific value of biogas: LHV vs HHV, typical ranges, and factors affecting its energy content for optimal system performance.

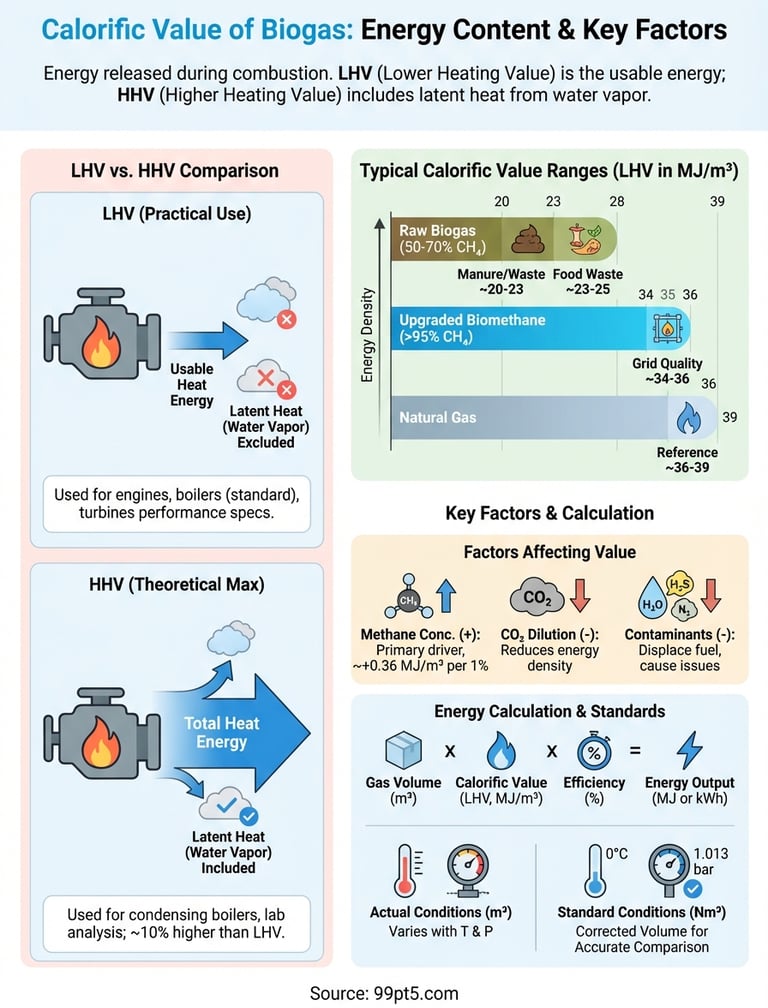

Calorific value tells you how much energy biogas releases when you burn it. Think of it as the fuel's power rating. Raw biogas typically delivers 20 to 28 MJ per cubic meter, depending on its methane content. This range matters because it directly affects how much electricity you generate, how much heat you produce, and whether your project hits its financial targets.

This guide breaks down everything you need to know about biogas energy content. You will learn the difference between lower heating value (LHV) and higher heating value (HHV), why both numbers exist, and which one matters for your equipment. We cover the typical ranges you can expect, the units you will encounter (MJ/m³, kcal/m³, Btu/ft³), and how to convert between them. You will see what changes biogas calorific value, from methane concentration to contaminants like CO₂ and H₂S. We also explain how upgrading raw biogas to biomethane transforms its energy content and why that matters for grid injection and vehicle fuel applications. By the end, you will have the practical knowledge to calculate, compare, and optimize the energy performance of your biogas system.

Why calorific value of biogas matters

Your biogas project's success depends on accurate energy calculations. When you know the calorific value of biogas, you can size equipment correctly, predict fuel costs, and estimate revenue from electricity or heat sales. Without this number, you are guessing at every critical decision. Your generator might be too small, your boiler might underperform, or your financial model might promise returns you will never see. Equipment manufacturers need the heating value to specify the right engine size, burner capacity, and fuel consumption rates. You need it to calculate how many cubic meters of biogas replace a liter of diesel or a cubic meter of natural gas.

Equipment selection and sizing

Every piece of combustion equipment requires a specific fuel energy input to deliver its rated output. Engines, boilers, and turbines all perform differently when you feed them biogas instead of natural gas or diesel. If you supply biogas with 20 MJ/m³ to an engine designed for natural gas at 36 MJ/m³, that engine will produce less power unless you increase the fuel flow rate. Your flow meters, pressure regulators, and injection systems all need sizing calculations based on actual calorific value. Get this wrong and your equipment will either starve for fuel or flood with excess gas that cannot burn efficiently.

Accurate calorific value data prevents costly equipment failures and ensures your system operates at design capacity.

Financial planning and revenue calculations

Your project economics live or die by energy output predictions. When you sell electricity to the grid, you receive payment per kilowatt-hour generated. That number comes directly from your biogas volume multiplied by its calorific value and your generator's conversion efficiency. A 10% error in assumed heating value translates to a 10% error in revenue forecasts. Banks and investors scrutinize these calculations before approving loans. Renewable energy certificates, carbon credits, and government incentives often require verified energy production data. You cannot claim these benefits without proving how much energy your biogas delivers.

How to work with calorific value in practice

You need three pieces of information to calculate energy output from your biogas system: the gas volume, the calorific value, and your equipment's conversion efficiency. Most operators measure volume in cubic meters per hour (m³/h) or per day (m³/day). The calorific value of biogas typically comes from lab analysis of your gas composition, specifically the methane percentage. Your equipment supplier provides the efficiency figure, usually between 30% and 45% for engines and up to 90% for boilers. Multiply volume by heating value to get total energy input, then multiply by efficiency to find useful energy output.

Calculating energy output from biogas flow

Start with your measured biogas flow rate in cubic meters per hour. If your digester produces 50 m³/h and your gas analysis shows 60% methane content, you can expect roughly 21.6 MJ/m³ heating value (LHV). Multiply 50 m³/h by 21.6 MJ/m³ to get 1,080 MJ/h total energy input. Converting this to kilowatts gives you 300 kW thermal input (since 1 kW equals 3.6 MJ/h). If you feed this gas to a generator with 38% electrical efficiency, you will generate approximately 114 kW of electrical power. This calculation method applies to any biogas application, whether you generate electricity, produce heat, or fuel vehicles.

Accurate flow measurement and regular gas composition analysis give you the baseline data every energy calculation requires.

Converting between different units

Engineers worldwide use different units to express heating values, and you need to convert between them for equipment specifications and performance comparisons. The most common units are megajoules per cubic meter (MJ/m³), kilocalories per cubic meter (kcal/m³), and British thermal units per cubic foot (Btu/ft³). One MJ/m³ equals approximately 239 kcal/m³ and roughly 26.8 Btu/ft³. Natural gas distributors often quote heating values in Btu per cubic foot, so when comparing biogas to natural gas, you must convert to the same units. A typical conversion shows biogas at 600 Btu/ft³ versus natural gas at 1,000 Btu/ft³, revealing that you need 1.67 m³ of biogas to replace 1 m³ of natural gas in terms of energy content.

Adjusting for real-world conditions

Your biogas system operates at specific pressure and temperature conditions that affect volume measurements and energy calculations. Standard conditions vary by region: Europe uses 0°C and 1.013 bar, while North America uses 60°F (15.6°C) and 14.7 psi. Volume measurements taken at different conditions require correction to standard conditions before you can apply published calorific values. Temperature changes affect gas density and apparent volume. A biogas stream at 40°C occupies more volume than the same mass of gas at 0°C, so your energy per cubic meter appears lower even though the total energy content stays constant.

Key definitions and standard conditions

Your calorific value measurements only make sense when you know the exact conditions under which they were taken. Biogas expands and contracts with temperature and pressure changes, which means the same mass of gas occupies different volumes under different conditions. Engineers created standard reference conditions to solve this problem, allowing accurate comparisons between measurements taken at different times, locations, and temperatures. When you see a heating value quoted as "21 MJ per Nm³," that Nm³ symbol tells you the volume was corrected to standard conditions. Without this correction, your energy calculations will be off by 10% or more depending on your local temperature and altitude.

Normal cubic meter (Nm³) vs actual cubic meter

The normal cubic meter (Nm³) represents the volume that gas occupies at standard conditions, while an actual cubic meter (m³) measures the volume at your current operating conditions. Your flow meter might show 100 m³/h of biogas at 35°C and 1.2 bar pressure, but when you correct this to standard conditions (0°C and 1.013 bar), the same gas becomes approximately 88 Nm³/h. This distinction matters because all published calorific value of biogas figures assume standard conditions. If you multiply your actual volume by the standard heating value without correction, you will overestimate your energy production by the same percentage that temperature and pressure inflate your volume reading.

Always verify whether your flow measurements show actual volume or standard volume before calculating energy output.

Standard reference conditions worldwide

Different regions use different standard conditions, creating confusion when you compare data from multiple sources. European standards (ISO 13443) define normal conditions as 0°C and 1.01325 bar, while North American standards often use 15°C (59°F) and 1.01325 bar. Australia and some other countries use 15°C as well. The petroleum industry sometimes uses 15.56°C (60°F) as standard. These differences mean a heating value published in Europe does not exactly match the same gas measured in North America. The temperature difference alone causes a 5.5% variation in volume between 0°C and 15°C measurements.

Your gas analyzer or flow computer should display which reference conditions it uses for corrections. Most modern instruments let you select the standard you need and automatically convert measurements. When you receive equipment specifications or compare published data, check the footnotes or technical specifications for the stated reference conditions. A biogas project using European equipment with North American engineering data needs careful unit conversions to avoid systematic errors in all energy calculations.

LHV and HHV for biogas in detail

Two different numbers describe the energy content of biogas: the lower heating value (LHV) and the higher heating value (HHV). The difference between them represents the energy locked in water vapor that forms when you burn biogas. Every cubic meter of methane produces roughly 2 kilograms of water vapor during combustion. This vapor carries away latent heat energy as it escapes up the exhaust stack. LHV ignores this lost energy and tells you only the heat available for useful work. HHV counts all the energy released, including the heat in the vapor, giving you a theoretical maximum that your equipment cannot actually deliver. Most practical applications use LHV because it reflects the real energy you can extract from biogas in standard engines, boilers, and turbines.

What LHV measures in biogas combustion

LHV gives you the usable heat energy available when biogas burns and the water vapor exits as a gas. Your engine or boiler exhaust typically stays well above 100°C, which means the water vapor never condenses and the latent heat escapes unused. For biogas with 60% methane content, the LHV typically measures around 21.6 MJ/m³. This number tells you exactly how much energy drives your generator's pistons or heats your boiler water. Equipment manufacturers specify fuel consumption and output ratings using LHV because it matches real operating conditions. When you calculate how many cubic meters of biogas your system needs per hour, you multiply the equipment's power output by its efficiency and divide by the LHV to get the required flow rate.

What HHV includes that LHV does not

HHV adds the latent heat of vaporization for all water produced during combustion, giving you a number roughly 10% higher than LHV for biogas. This extra energy only becomes available if you cool the exhaust below 100°C and recover the heat released when water vapor condenses back to liquid. For that same 60% methane biogas, HHV might reach 23.9 MJ/m³ instead of 21.6 MJ/m³. Condensing boilers and some specialized heat recovery systems can capture part of this latent heat, achieving efficiencies above 90% when calculated against LHV. Laboratory measurements often report HHV because the calorific value of biogas testing procedures run under controlled conditions that allow complete heat recovery.

LHV reflects the energy your equipment actually delivers, while HHV shows the theoretical maximum if you could recover all heat from water vapor.

Which value your equipment actually uses

Your equipment specifications almost always quote performance based on LHV, especially for engines and standard boilers. Generator datasheets show electrical output per cubic meter of biogas assuming the LHV value. If you see fuel consumption listed as "0.45 m³/kWh" for a biogas engine, that calculation uses LHV, not HHV. Using HHV numbers in your calculations will make your system appear 20-25% more efficient than it actually operates, leading to undersized gas storage, incorrect flow meters, and disappointed financial projections. The exception comes with condensing boilers specifically designed to recover latent heat. These systems can achieve 95-105% efficiency when you calculate against LHV, or about 85-95% against HHV. Natural gas distributors in North America often quote HHV, while European suppliers typically use LHV, so you must verify which value appears in specifications before comparing biogas performance to natural gas benchmarks.

Typical calorific value ranges and benchmarks

Raw biogas from anaerobic digesters typically delivers 20 to 28 MJ/m³ (LHV), though the exact value depends entirely on methane concentration. Your gas composition determines where you fall in this range. Biogas with 50% methane yields roughly 18 MJ/m³, while 70% methane pushes you to 25 MJ/m³. Pure methane delivers 36 MJ/m³, setting the theoretical upper limit. Most agricultural digesters processing animal manure produce biogas with 55-65% methane content, placing your calorific value of biogas between 20 and 23 MJ/m³. Industrial organic waste and food processing residues can push methane content higher, sometimes reaching 70% or more, which brings heating values closer to 25 MJ/m³.

Raw biogas from different feedstocks

Animal manure digesters generate biogas with 20-22 MJ/m³ heating value on average. Cattle manure typically produces gas at the lower end of this range (55-60% methane), while pig and poultry manure can reach 60-65% methane, giving slightly higher energy content. Landfill gas usually contains 45-55% methane, translating to heating values of 16-20 MJ/m³, making it the weakest biogas source. Food waste and crop residues often deliver the strongest raw biogas, with 65-70% methane content producing 23-25 MJ/m³. Wastewater treatment plant digesters fall somewhere in between, typically generating 18-21 MJ/m³ depending on the organic loading and operating temperature.

Biomethane and grid-quality gas standards

Upgraded biomethane must meet natural gas pipeline specifications, which typically require at least 95% methane content. This upgrading process raises your heating value to 34-36 MJ/m³, essentially matching conventional natural gas at 36-39 MJ/m³. Grid injection standards vary by country but generally demand methane purity above 95%, CO₂ below 2-3%, and oxygen under 0.5%. Your upgraded biogas at 97% methane delivers approximately 35 MJ/m³, making it functionally identical to natural gas for all practical applications.

Upgrading raw biogas to biomethane nearly doubles the energy density, transforming a variable fuel into a standardized grid-compatible product.

Comparison with conventional fuels

Natural gas provides your baseline comparison at 36-39 MJ/m³, meaning you need roughly 1.7 cubic meters of raw biogas (60% methane) to match one cubic meter of natural gas energy content. Diesel fuel contains 36 MJ per liter, so 1 liter of diesel equals approximately 1.7 m³ of raw biogas or 1.0 m³ of upgraded biomethane. Propane delivers 25.3 MJ/liter, making it easier to replace with raw biogas on a volume basis. Your biogas vehicle needs a fuel tank nearly twice as large as a natural gas vehicle to achieve the same driving range when using raw biogas instead of upgraded biomethane.

Factors that change biogas calorific value

Your biogas composition changes constantly based on what enters your digester and how your system operates. These variations directly affect your energy output and system performance. The calorific value of biogas shifts up or down depending on methane concentration, contaminant levels, and operating conditions. Understanding these factors lets you predict performance, troubleshoot problems, and optimize your digester for maximum energy production. Your gas composition determines whether you meet equipment specifications, comply with grid injection standards, or need additional cleaning before use.

Methane concentration drives energy content

Methane percentage determines your heating value more than any other single factor. Each 1% increase in methane content adds approximately 0.36 MJ/m³ to your biogas energy density. When your digester produces gas with 55% methane instead of 65%, you lose roughly 3.6 MJ/m³ of heating value, which means 17% less energy from the same gas volume. Digester temperature affects methane production significantly. Mesophilic digesters (35-37°C) typically generate 58-62% methane, while thermophilic systems (50-55°C) can push methane content to 65-68%. Your feedstock composition also matters because protein-rich materials produce more methane per kilogram than carbohydrate-heavy substrates.

Carbon dioxide dilution effect

CO₂ occupies space in your biogas without contributing any combustion energy, effectively diluting the methane and reducing heating value per cubic meter. Raw biogas typically contains 30-45% CO₂, which means nearly half your gas volume provides zero fuel value. Higher CO₂ concentrations lower your energy density proportionally. A digester producing gas with 40% CO₂ instead of 35% delivers 5% less energy per cubic meter, even if the absolute methane quantity stays constant. Your organic loading rate and digester pH influence CO₂ levels. Overloading your digester or letting pH drop below 6.8 increases CO₂ production and reduces overall heating value.

Every percentage point of CO₂ you remove from biogas adds roughly 0.36 MJ/m³ of usable energy density.

Contaminants and trace gases impact

Water vapor saturates your raw biogas stream at digester temperature, typically carrying 5-7% moisture content that displaces combustible gas. This moisture reduces your effective heating value by the same percentage until you remove it through cooling or drying. Hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) levels between 500-5,000 ppm contribute minimal energy but create serious corrosion problems in engines and pipelines. Nitrogen contamination from air leaks dilutes your gas without burning, dropping your heating value proportionally. Your system's airtightness directly affects nitrogen content. Siloxanes from industrial waste or wastewater treatment plant biogas do not significantly change heating value but damage equipment by forming silicon dioxide deposits during combustion.

From raw biogas to biomethane energy content

Upgrading transforms your raw biogas into biomethane, a process that removes CO₂ and contaminants to concentrate the methane content above 95%. This concentration step fundamentally changes your fuel characteristics, nearly doubling the energy density from roughly 21 MJ/m³ to 35 MJ/m³. Your upgraded gas becomes interchangeable with natural gas, opening access to pipeline injection, vehicle fuel markets, and applications that demand high-purity methane. The upgrading investment pays off through higher energy sales prices, reduced transportation costs per unit energy, and access to premium markets that raw biogas cannot serve.

The upgrading process fundamentals

Your biogas upgrading system removes CO₂ as the primary task, reducing carbon dioxide from 35-45% down to 2% or less. Water scrubbing, pressure swing adsorption, membrane separation, and chemical absorption all achieve this goal through different mechanisms. Water scrubbing dissolves CO₂ in water under pressure, then releases it when pressure drops. Membrane systems use selective permeability to separate methane from smaller molecules. Each technology delivers different energy penalties, capital costs, and methane recovery rates. Your choice depends on biogas volume, required purity, and available utilities like electricity and water.

The upgrading process also removes water vapor, hydrogen sulfide, siloxanes, and trace contaminants that prevent pipeline injection or damage equipment. Activated carbon beds capture siloxanes and other organic compounds. Dessicant dryers reduce moisture to pipeline specifications, typically requiring dew points below minus 20°C. Your complete upgrading system includes multiple treatment stages, each targeting specific contaminants. Hydrogen sulfide removal often occurs before the main upgrading step because H₂S interferes with some CO₂ separation processes and damages equipment materials.

Upgrading removes roughly 35-40% of your raw biogas volume as separated CO₂, but the remaining methane contains nearly twice the energy density per cubic meter.

Energy density transformation through upgrading

Your calorific value of biogas jumps from 20-23 MJ/m³ in raw form to 34-36 MJ/m³ after upgrading to 97% methane purity. This transformation means you move 1.6 times more energy in the same pipeline volume or storage tank. A truck carrying compressed biomethane at 250 bar delivers the equivalent energy of two trucks carrying raw biogas at the same pressure. Your distribution costs per megajoule drop proportionally. The energy required to compress biomethane to vehicle fuel pressure (200-250 bar) represents a smaller fraction of the total fuel energy compared to compressing raw biogas because you compress fewer cubic meters for the same energy delivery.

Economic and practical implications

Pipeline injection requires biomethane quality, not raw biogas, because natural gas infrastructure serves millions of customers with equipment calibrated for consistent fuel properties. Your upgraded gas meets Wobbe index specifications, ensuring proper combustion in domestic appliances and industrial burners. Grid access lets you sell energy at natural gas market prices, typically 50-100% higher than electricity prices on an energy-equivalent basis. Vehicle fuel applications demand upgrading because storage tanks must be reasonably sized and fueling stations need standardized pressure and purity specifications.

Raw biogas works well for on-site combined heat and power applications where you can use the gas immediately after basic cleaning. Your generator burns the CO₂-rich mixture without problems because engine combustion chambers tolerate inert gas dilution. Heat applications like boilers and direct thermal uses also accept raw biogas efficiently. The upgrading decision depends on whether you value the flexibility and premium pricing of biomethane enough to justify the capital investment and operating costs of purification equipment. Projects located far from gas grids or with strong on-site energy demand often skip upgrading and maximize raw biogas utilization locally.

Key points to remember

The calorific value of biogas ranges from 20 to 28 MJ/m³ for raw gas and reaches 34-36 MJ/m³ after upgrading to biomethane. You calculate energy output by multiplying gas volume by heating value and equipment efficiency. LHV gives you usable energy in practical applications, while HHV includes theoretical heat you cannot capture in standard equipment. Methane concentration drives your heating value more than any other factor, with each 1% increase adding roughly 0.36 MJ/m³. Your measurements must reference standard conditions (Nm³) to ensure accurate comparisons and calculations.

Upgrading doubles your energy density and opens access to pipeline injection and vehicle fuel markets. If you need biogas processing equipment that guarantees maximum energy recovery, explore the 99pt5 BioTreater™ system designed for 99.5% methane recovery and the lowest operating costs in the industry.